Turning Iron and Steel Manufacturing Waste Into Valuable Materials

China currently manufactures half of the world’s iron and steel through a process that leaves enormous amounts of waste, or slag, to accumulate in landfills or in stockpiles out in the open where its toxic elements may cause environmental and health problems. In partnership with a major iron and steel company in China, two Columbia engineering researchers hope to repurpose some of this slag for use in a range of industries, including paper, plastic, paint, cement, oil, and gas.

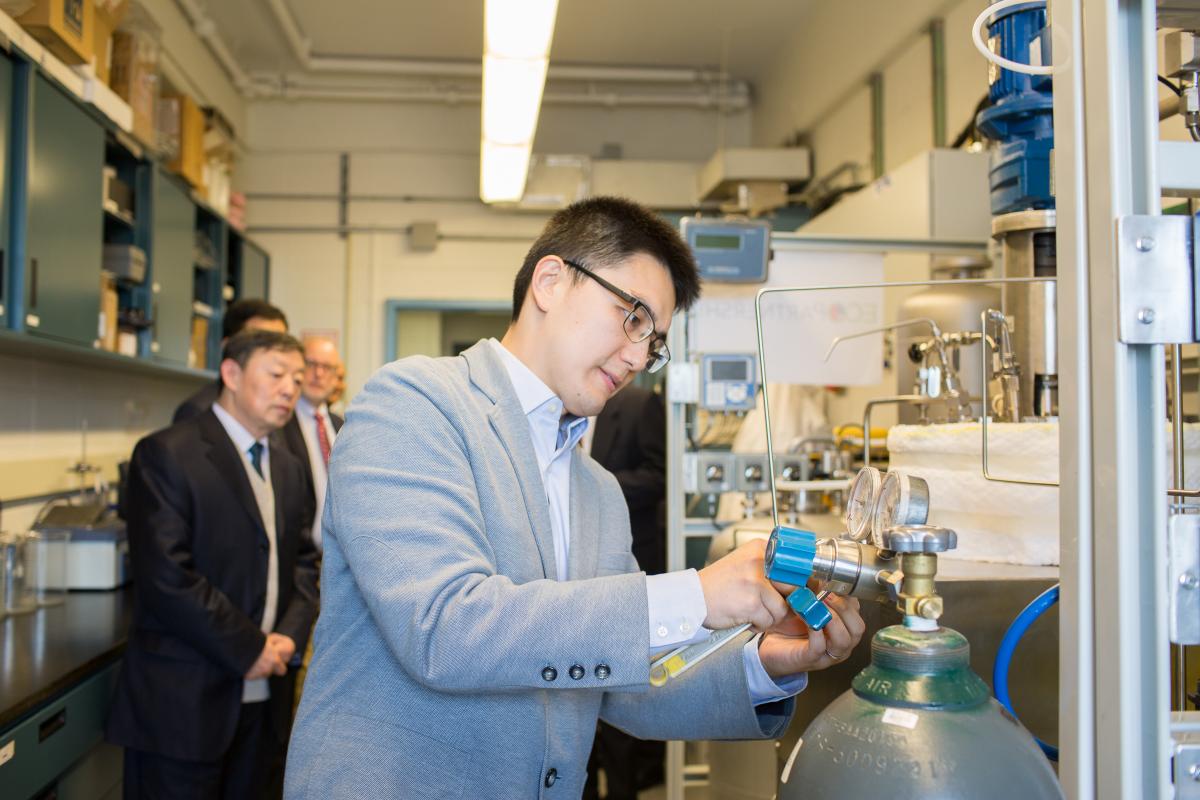

In late December 2016, executives from China’s Baotou Iron and Steel (Group) Co. visited the Columbia Engineering lab of Ah-Hyung (Alissa) Park and Xiaozhou (Sean) Zhou to see the operation of a prototype processing unit designed by Park and Zhou to repurpose slag. Their goal is to turn wastes of steel and iron manufacturing into reusable materials through a chemical process that integrates the processes of mineral carbonation and rock weathering. They also hope to reduce overall carbon emissions by using industrially emitted carbon dioxide (CO2) as one of the reactants.

“We are working with Baotou Steel on an exciting project that uses our carbon sequestration technology to treat their iron and steel slag,” says Park, associate professor of earth and environmental engineering and chemical engineering and director of the Lenfest Center for Sustainable Energy. “The techniques we’ve developed have the potential to make iron and steel manufacturing substantially more sustainable—not only in China but globally.”

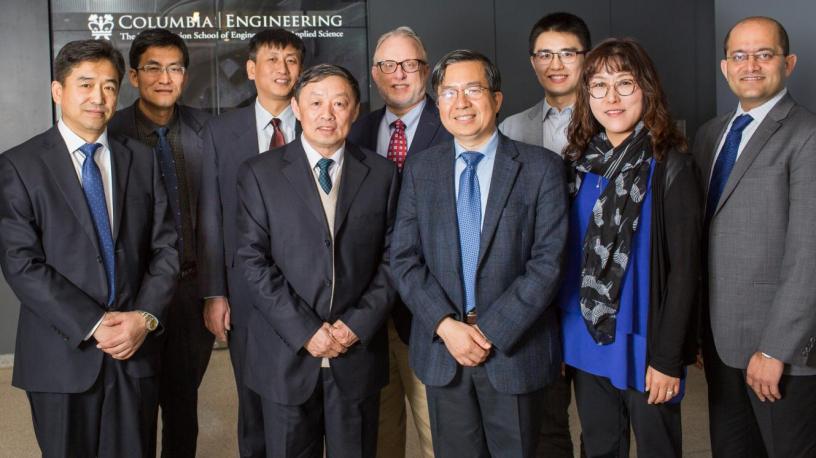

Officials from Baotou Iron and Steel (Group) met with Columbia Engineering faculty and toured the lab. Left to right: Jianzhong Cheng, Gangsheng Wu, Wenjian Yu, and Yizhong Wang of Baotou Steel; Scott Smouse, an advisor to the U.S. Department of Energy; Shih-Fu Chang, Xiaozhou (Sean) Zhou, and Ah-Hyung (Alissa) Park of Columbia Engineering; and Vatsal Bhatt of Brookhaven National Laboratory.

The visit was part of an EcoPartnership program between the United States and China that was announced in 2015. Representatives from Columbia Engineering and Baotou Steel, one of China’s largest steel companies, were joined by Scott Smouse, senior advisor to the deputy assistant secretary for clean coal and carbon management at the U.S. Department of Energy, and Vatsal Bhatt, senior energy policy advisor at Brookhaven National Laboratory who is also member of the EcoPartnership Secretariat. To design and fabricate the prototype, Park, whose research is focused on developing ways to capture CO2 from industrial sources before they enter the atmosphere, worked closely with Zhou MS’11, MPhil’14, PhD’15, the project’s leader who developed the slag-conversion process and is an associate research scientist in the department of earth and environmental engineering.

The researchers hope to be able to reach zero-waste by comprehensively using as much of Baotou Steel’s slag as they can. “We expect that this will reduce the amount of land used to stockpile slag, clean up landfills, and convert the waste into valuable products for several other industries,” Zhou says. “Maximizing the overall sustainability of the iron and steel industry and improving how we use resources and materials could be transformative.”

The prototype unit is expected to produce a wide range of usable materials from Baotou slag and carbon dioxide. The project leaders have formed a Columbia spinoff startup, GreenOre CleanTech LLC, through Columbia Technology Ventures, and are working on their project's next phase: designing the first commercial pilot plant, which is planned to be 500 times the size of the prototype in the Columbia Engineering lab. That plant is scheduled to be built in Inner Mongolia, China, over the next year and to go into operation by mid-2018.

“Our timing has been perfect,” notes Zhou, whose project received seed funding and mentoring from the School's Translational Fellows Program. “There is an urgent need for appropriate treatment of slag by Chinese iron and steel companies, especially since these organizations are facing stricter environmental regulations and the costs of industrial land use are rising. At the same time, the mineral carbonation technology using wastes has made major advances around the world and this Columbia technology has a very promising technical and economic feasibility.”

The project is especially timely for Park’s group at Columbia Engineering, which is focused on investigating the reaction pathways that allow the production of high-value materials from mineral or industrial waste using industrially emitted CO2. “Our ultimate goal is to change people’s views on wastes, whether industrial or domestic.” She says. “By engineering these unconventional ‘green ores’ into valuable products, we can effectively utilize them in our industries, and this will improve the overall sustainability of the production of industrial commodities.”